By Matt Kelly

According to Circular 0047/2015, issued in September 2015 by the Department of Education and Skills, every primary and post-primary school in the Republic of Ireland was to be presented with the national flag and a copy of the 1916 Proclamation in England and Irish. ‘It is intended’, the circular explains, ‘that the schools will retain the flag and display it prominently on “Proclamation day”, 15th March 2016.’ The flag and proclamation were to be presented to each school by a member of the Defence Force in a twenty-minute ceremony that would involve a reading of the Proclamation and an outline of the history of the flag along with its formal presentation. Teachers are to be issued a booklet outlining flag protocol. Post-primary schools will receive the flag and a copy of the Proclamation from the Thomas Francis Meagher Foundation—Meagher is credited with first flying the Irish tricolor at Waterford during 1848. A further circular of January 2016 suggests that an ‘ideal start to the events in a school on Proclamation Day would be a flag-raising ceremony, playing or singing the National Anthem and perhaps a reading of the Proclamation by teachers and/or students.’

The government’s decision to issue guidance rather than instruction, allowing local communities to decide how to shape their commemoration of the 1916 Rebellion, should not obscure the lead it has taken. This is an exceptional initiative that comes from the heart of government. It will incur a considerable financial cost. Head-teachers will surely feel obliged to toe the line. No one can predict if Proclamation Day will become a fixture of the Irish year, but it is clear that the government expects each school to keep the national flag appropriately for future use. Are we seeing the ‘invention of tradition’? Will Ireland’s children be summoned to the flag every year?

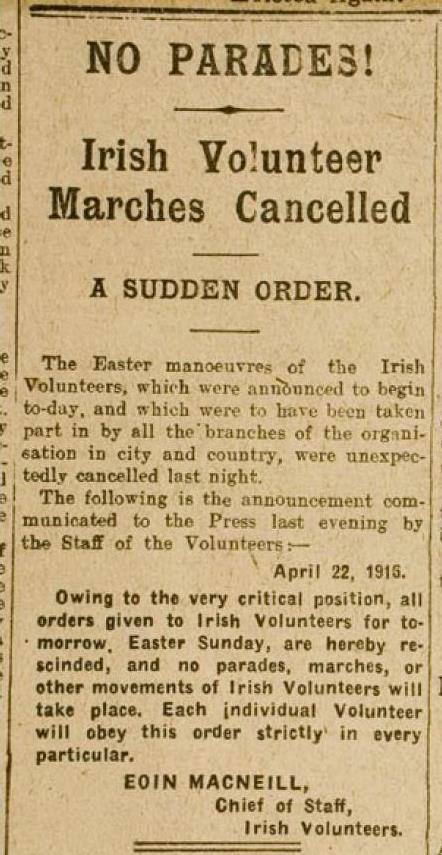

I think the school children of Ireland should be reading the Proclamation alongside Eoin MacNeill’s Memorandum of March 1916. MacNeill was a republican, he believed the Irish people had the right to bear arms, he was the Volunteer Chief of Staff – the highest ranked officer in the organization – and he considered the formation of the Irish Volunteers to be a sovereign act by the Irish people. He believed the Volunteers had the right to resist by force any attempt of the British government to disarm them. He was also, of course, responsible for the notorious countermand of Easter Saturday. Most of the arguments we hear against the rising tend to be from those who believe the Home Rule campaign still had potential. MacNeill was not a home ruler. As such, no serious-minded republican, however moved by the heroism of Easter Week, should casually dismiss his arguments.

Before looking at MacNeill’s argument, let’s say first of all that the 1916 Proclamation is a remarkable document, constituting an audacious mix of traditional nationalist thinking and liberal or civic ideals. It was exceptional in being addressed to ‘Irishmen and Irishwomen’ and there was no question many of rebels supported women’s suffrage. Additionally, the Proclamation was a genuinely radical document, although to my mind it was not nearly as radical at the 1867 Fenian Proclamation. It sought to protect civil and religious liberties; socialist connotations were oblique but manifest in the reference to ‘the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland’, which strongly echoed the 1914 constitution of the Irish Citizen Army; and the celebrated intention to cherish ‘all the children of the nation equally’ signalled a desire to overcome the sectarian ‘differences carefully fostered by an alien government’.

At the same time, the rebels claimed to act in ‘the name of God and of the dead generations’ from which Ireland received ‘her old tradition of nationhood’, reminding us that they were not, on the whole, either secularists or revolutionaries seeking to proclaim Year 1. Indeed, note the uncanny echo of Marx’s claim in The Eighteenth Brumaire that ‘Tradition from all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living’. The Fenians, incidentally, had insisted on the separation of church and state. But note also the claim from the Proclamation that ‘The Irish Republic is entitled to, and hereby claims, the allegiance of every Irishman and Irish woman.’ This is extraordinarily authoritarian and surely at odds with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. Except, of course, this doesn’t matter, for despite frequent airy claims to the contrary, the Proclamation is not the founding document of the Republic of Ireland. It has no legal status. It does not describe the rights or the obligations of a citizen of the Republic and it cannot be appealed to in the courts. Irish men and woman, both sides of the border, nationalist or unionist, and notwithstanding the current brouhaha, can happily ignore it.

And I suspect many of Ireland’s school children will do just that. But some might well be caught up in commemoration fever and should they take a break from Call of Duty or Assassin’s Creed, they should study the thoughts of Eoin MacNeill before getting too excited about Pearse and Clarke.

As has been repeated ad nauseam, the rebels of 1916 represented only a small proportion of the Irish population, a minority of the republican separatist minority. Success was unlikely and the leadership knew it. The rising, it is claimed, was an event whose meaning was not to be found in the outcome but in the gesture, the ‘propaganda of the deed’; this was rebellion as act of witness, rather than serious military enterprise. And it has become an established trope of much analysis of Easter Week to emphasise its theatrical or performative aspects.

But actors don’t kill or get killed in the theatre. We need to be careful to distinguish useful ways of thinking about the rebellion historically, about the mentalité of the participants, from what MacNeill considered the moral burden carried by the rebels.

The memorandum runs to eleven handwritten pages. The exact circumstances of its composition are not known, but it seems to have been written in March 1916 in response to heightened Volunteer activity and MacNeill’s growing fear that the organisation was increasingly out of his control. His fears proved well founded. The rebellion began with something approaching a palace coup and constituted a gross act of insubordination by his officers. One wonders what the senior command of Ireland’s Defence Forces make of that.

MacNeill makes a strongly consequentialist case against rebellion, arguing that a rebellion would be ‘morally wrong’ if its principal instigators knew it stood little chance of success: those responsible for the act would thus ‘incur the guilt not only of that action itself but of all its direct consequences.’ To kill anyone under such circumstances would be ‘murder’. He also argues that the potential success of the rebellion can only be calculated in terms of its likely actual and immediate consequences, rather than ‘some future moral or political advantage which may be hoped for as the result of non-success.’ MacNeill’s position is that one cannot morally take the life of another on the grounds that this might trigger a succession of events that will retrospectively justify the original act.

As such, a rebellion could be justified when based on ‘actualities’ rather than ‘instinctive feeling or premonitions or on the adoption of a priori maxims’. Feeling or instinct, MacNeill insists, gives no ‘justification for any deliberate course of action involving moral responsibility.’ A man who cannot give a ‘reasonable account’ of a proposed action must be allowing ‘instinct’ to override ‘judgement’. To issue orders arrived at through instinct cannot be morally justified.

MacNeill moves from this abstract reasoning to deconstruct three a priori maxims that seem to be propelling his comrades towards an immoral action. They are, first, ‘it is essential that Ireland take action during the present war’, second, ‘Ireland has always struck the blow too late’, and, third, ‘in military matters the advantage lies with the side that takes the initiative (or the aggressive).’ The first two of these claims reflect long-established Fenian arguments. MacNeill bluntly states that to act on these terms without taking account of ‘actualities’ would be ‘proof of mental incapacity’. MacNeill then addresses the notion that action is needed ‘to produce an ultimate effect on the national mind’ on the grounds that the destruction of Irish nationality is imminent. Here MacNeill goes some way towards agreeing with his comrades. If Irish nationalism was so imperilled, an act of self-sacrifice could be rationalised, only MacNeill doesn’t believe Irish nationality to be so at risk.

Why then do some of his comrades in the volunteers appear intent on rebellion? MacNeill’s answered this question with some of the most psychologically penetrating words written during the revolution.

To my mind, those who feel impelled towards military action on any of the grounds that I have stated are really impelled by a sense of feebleness or despondency or fatalism, or by an instinct of satisfying their own emotions or escaping from a difficult & complex & trying situation. It is our duty, if necessary, to trample on our personal feelings and to face every sort of difficulty and complexity, and to think only of our country’s good.

Any celebrant of the 1916 Rebellion, or indeed any advocate of revolutionary violence, cannot afford to casually dismiss these lines.

MacNeill’s argument now took a more practical turn, seeking to find a logical explanation in current events. He asks why the British have allowed the Volunteers to grow until they are capable of mounting a rebellion. A premature rebellion would divide nationalists against each other and give unionists in the North an excuse to mobilise, thereby creating the opportunity for the British to intervene to prevent carnage, justifying for the first time a strengthening of the British state in Ireland. This probably allowed Dublin Castle too much percipience. Still, to avoid this happening, MacNeill argues that the Volunteers must continue to organise themselves, strengthening the ranks and demonstrating their resolve, all the while recognising that their purpose is not to fight but to ‘secure Ireland’s rights and liberties’.

This was a vital aspect of MacNeill’s case against rebellion. He believed the existence of the Volunteers had fundamentally undermined Britain’s capacity to govern Ireland through the normal channels of civil society. In essence, the police could no longer suppress the Volunteers, which meant Britain could only assert its former authority through military means. This had created a stalemate, giving the Volunteers further scope to extend their organisation, which would further undermine the capacity of the British state to exert control over Ireland. Thus, MacNeill’s case against rebellion does not rest on the judgement that the Volunteers were not yet sufficiently strong to mount a successful rebellion, but that it was plausible to suppose that to continue strengthening the organisation could see the object of a rebellion met without the need for a shot to be fired—or for a murder to be committed. This takes us into the realm of the historical counter-factual and it is impossible to say whether MacNeill was right or wrong, but his thinking chimed with popular ideas about how the Irish Volunteers of 1782 helped bring Grattan’s parliament into being.

What we do know is that MacNeill was a democrat who was convinced that Irish public opinion was coming around to the separatist point of view. This made it all the more important that the separatists should not act as though they had a monopoly on truth but should continue to work for the outcome they sought. To do effectively, they must ‘remember that what we call our country is not a poetical abstraction, as some of us, perhaps all of us, in the exercise of our highly developed capacity for figurative thought, are sometimes apt to imagine … What we call our country is the Irish nation, which is a concrete and visible reality.’

MacNeill, of course, didn’t have the monopoly on truth either, and some might not consider him much of a moral philosopher. But any school child able to make sense of the 1916 proclamation is capable of making sense of MacNeill’s arguments. Rather than summoning every Irish school child to the flag, as the government seems wont to do, might it not be preferable to make Proclamation Day an opportunity to have them think about what might or might not constitute a moral act?