By Joep Leerssen

the German army in late August 1914.

For the past years, I have been working on French-German enmity over Alsace-Lorraine between 1840 and 1914, and the continuity of that enmity, and the agency of intellectuals maintaining that continuity: Quinet, Venedey, Mommsen, Fustel de Coulanges, Strauss, Treitschke, Renan, Thomas Mann, Durkheim. It is remarkable to see how the role of Britain changes in that battle of public opinions: from the support voiced for Germany in 1870 (Max Müller, Carlyle) to the anti-German propaganda set up in 1914 and the anti-German war efforts of the Trevelyans, Thomas Hardy, Ford Madox Ford, even H.G. Wells, alongside stalwarts such as John Buchan and Rudyard Kipling. To observe how very intense nationalist feelings were in Britain in these years, and how they were whipped into a frenzy by the European conflagration, is nothing new; but it is not usually foregrounded in our analysis of the Easter Rising.

One side effect of that war hysteria all over Europe (it has been excellently documented in a Dutch study which merits an English edition: Ewout Kieft’s Oorlogsenthousiasme, 2015) was something of which we are becoming increasingly aware: the strange death of Utopian Idealism. With some laudable exceptions (Shaw), all the vegetarians, the anti-vivisectionists, the hygienists, all the Arts and Crafts and Slade School children of William Morris, all lost it in August 1914. Fervently, hysterically, reformists and conservatives alike greeted the Great War as a cathartic crisis. Pearse’s notorious words about the need for a bloodbath to rejuvenate Old Mother Europe’s barren spirituality was on a par with what Rupert Brooke was feeling and writing, and D’Annunzio in Italy, and Péguy in France, and Thomas Mann in Germany. A general fey-heroic, sanguinary high-mindedness can be encountered among the artists and intellectuals of London, Munich, Berlin, Vienna and Paris, melting into the crowds singing Rule Britannia, the Wacht am Rhein or the Marseillaise in the streets.

At the same time we have become aware of the extent to which 1916 was prepared, not just by Fenians and radicalized Irish-Irelanders, but also by Irish participation in Europe’s post-Morris Utopian Idealism: from the printing press of the Yeats sisters to the tableaux vivants and amateur theatricals of Inghinidhe na hÉireann. Roy Foster’s Vivid Faces does a splendid job in drawing attention to it, but sees it falter as a result of the Rising and the rising tide of reactionary nativism in Irish national politics.

I believe that that tide turned not in 1916, but in August 1914 when, following the ‘Strange Death of Liberal England’, a wedge was driven between the Dublin Utopian Idealists and their like-minded spirits in London and Paris. Irish literary and linguistic revivalism could, earlier on, fit into the Morris reformist spectrum and easily ally itself to suffragette hunger strikers and like-minded reformers in London. Fin de siècle Paris was the birthplace of the Irish Literary Revival, which drew on Maeterlinck and Ibsen as much as on Cúchulainn and Deirdre. The hunger strike as evoked in Yeats’s At the King’s Threshold was first put into practice by the suffragette Marion Wallace Dunlop, a co-activist of the Gore-Booth sisters.

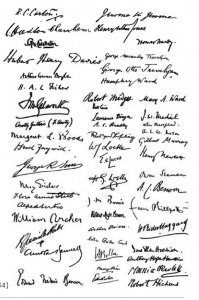

under a manifesto denouncing Germany,

reproduced in facsimile in the New York Times,

September 1914. The writers had been convened by the

freshly established Propaganda office.

The writers had been convened by the

freshly established Propaganda office.

Two Joyce characters, one from ‘The Dead’ and one from Ulysses, come to mind. The Gaelic revivalist Miss Ivors would have got on famously with Haynes, the Celtophile English guest in the Martello Tower. But that was in a 1904 setting. After 1914, that thought experiment becomes inconceivable.

What made the difference was above all British jingoism: the fervent, war-fanned combination of British imperialism and English nationalism. It was this, more than anything, that starved Irish revivalists from solidarity in Britain. Irish nationalism was forced into isolationist nativism, not only by its post-Victorian admiration for Germany (which lingered here longer and stronger than in Edwardian England); nor by an ascendancy of its own inner reactionary forces (and there was plenty of traditionalist anti-cosmopolitanism among the Irish Irelanders, in spite of what sympathetic historians may choose to highlight in these centenary celebrations); but also by the increasing shrillness and chauvinism of English nationalism and British imperialism post-1914.

The Netanyahu-style overkill in repressing Pearse’s operetta rebellion is a case in point. It is a universally accepted truism that the separatist ideals of 1916 would never have obtained popular sympathy among the Irish populace if it had not been for the wholesale destruction of the area around the GPO and the bloody-minded executions of the 1916 leaders. That bloodymindedness is accepted as a given, a matter of course: don’t you know there was a war on? But no. It was more than a mere inert, ambient fact of life: it was an ideology, a mind-set, an agency. It was what enlisted the likes of Buchan, Barrie, Kipling and Wells for a propaganda war against the “Huns”; it produced the notorious Bryce Report on ghoulishly exaggerated German cruelties – and it shared a see-saw with Irish nationalism. And in the process it stripped Irish nationalism of its redeeming pre-1914 qualities: its links with a progressive European utopianism.